Common sense and the FAR: a match much below heaven

Several recent executive orders promise to reform federal acquisition, notably “Restoring Common Sense to Federal Procurement.” If only it were so easy.

The FAR unloved

The FAR is long at over 2,000 pages, but the FAR council promulgates a lot of regulations from statute. Congress regularly uses the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and other must pass legislation for procurement riders, embedding lagging congressional “remedies” into law.

The FAR’s organization is quirky, but many will find themselves mostly returning to the same sections. Notably, the FAR applies only to federal actors, and especially contracting officers; the government must include FAR provisions and clauses in solicitations and contracts, respectively, to bind contractors. To streamline this process, the FAR includes a clause and provision matrix, mapping required and optional contract terms by contract type and other attributes.

And yet, I often see FAR clauses that do not belong in the same contract. GSA Schedule orders inherit FAR Part 12’s streamlined contract provisions and clauses from the vehicle; there’s a specific deviation of 52.212-4, which consolidates commercial-specific terms for invoicing and acceptance, payment terms for fixed price and hourly contracts, terminations, and more. For example, 52.232-7, Payments under Time-and-Materials and Labor-Hour Contracts, is duplicative with the T&M payment clause in 52.212-4. Why, and how can acquisition reform address?

Infamously, the FAR Part 15 process model for negotiated procurement, when released in 1998, lacked specificity that GAO and other courts filled in. See, especially, clarifications and discussions. These Part 15 procedures and their common law supplemental rules—while not required for GSA Schedule buys, IDIQ orders, or commercial-item procurements—apply when the government uses Part 15 language in the solicitation, such as mention of clarifications and discussions. Understanding court decisions’ effect on how to conduct procurements is further complicated by multiple tribunals that may disagree with one another.

Fragmented dispute resolution

The US government has sovereign immunity, meaning it can only be sued where and when it consents to be. The following are the most common dispute resolution forums in federal acquisition, comprising federal courts; GAO, a branch of Congress; and agency departments:

- Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals, operated by DOD, for DOD and NASA, pursuant to the Armed Services Procurement Act, to resolve contract management, rather than award, issues

- Civilian Board of Contract Appeals, operated by GSA per the Contract Disputes Act for the same purposes as the ASBCA

- Court of Federal Claims, a Congressional court authorized to hear most monetary claims against the government, including bid protests

- GAO, a protest tribunal operated by Congress that issues nonbinding findings, which may disagree with COFC findings

- Office of Dispute Resolution for Acquisition at the FAA, which uses its own acquisition regulation called AMS

- Postal Service Board of Contract Appeals, for Postal Service contracts

- Postal Regulatory Commission for Postal Regulatory Commission contracts

- SBA”s Office of Hearing and Appeals, which decides quasijudicial matters related to SBA decisions, such as size and socioeconomic determinations

- Tennessee Valley Authority Board of Contract Appeals (TVABCA), whose creating statute allowed for its own tribunal

- US District Courts and Appellate Courts, the “traditional” federal judiciary created by Article 3 of the constitution authorized to hear civilian and criminal trials and allows for jury decisions; as a rule, judges decide matters of law, while juries decide matters of fact

Another wrinkle: the Christian Doctrine, which holds that certain contract clauses deeply rooted in federal procurement policy, such as terminations for convenience, are incorporated into government contracts by law, even where omitted by the contracting officer by mistake. Any FAR section covered by Christian would likely remain in future procurement regulation.

Executive orders for change

The “common sense” EO states US acquisition policy is “to create the most agile, effective, and efficient procurement system possible.” The FAR Council now has 180 days to work with agency heads and others to remove FAR elements not required by statute. I assume someone will review case law. Agencies will streamline their FAR supplements (looking at you, DOD).

And then?

Across government, will every contract be modified with new clauses? Will a reduced contracting corps rapidly ingest the changes and optimize processes, documentation, and decision criteria?

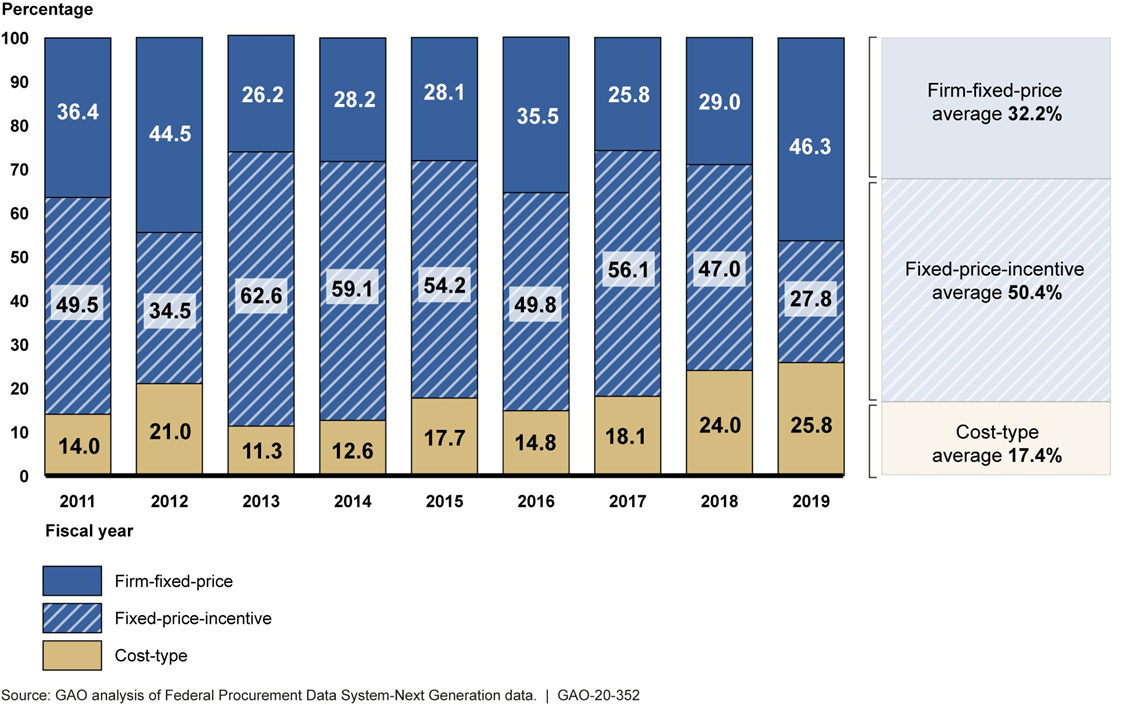

In the 1960s, Robert McNamara, also leveraging his automotive experience to improve government efficiency, pushed DOD to move from onerous cost-type to fixed price contracts. In 2009, Congress tried again, passing the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act, which became the Better Buying Initiative. GAO reported on progress moving to fixed price contracts in a 2020 report, “Procedures Needed for Sharing Information on Contract Choice among Military Departments” (see figure). The numbers moved in the wrong direction, with cost-type contracts increasing from 14.0% in 2011 to 25.8% in 2019.

A case for modesty

Increasing acquisition efficiency cannot be accomplished by reforming procurement rules alone; the federal budget cycle and availability of funds are complicating matters. This is especially true when programs must clear big-A acquisition review gates (eg, DOD 5000, DHS Acquisition Lifecycle Framework) timely. Any changes to the FAR should be mindful of these realities and provide contracting teams and programs tools to keep acquisitions on track.

This doesn’t require a regulatory rewrite, although drastically increasing the simplified acquisition and TINA thresholds (the latter being the dollar amount above which a modification requires certified cost or pricing data), and removing subpart 16.5’s preference for multiple award IDIQs, would be a good start.

Federal acquisition could benefit from an official best practices playbook that lays out court-tested approaches to streamline procurement. A model is DHS”s Procurement Innovation Lab, which makes its DHS PIL Tested Innovation Techniques available online. This includes techniques such as:

- Highest technically rated with a fair and reasonable price (HTRORP on PTAI): Accelerate the source selection for multiple-award contract vehicles by evaluating all technical proposals and then award to the highest rated offerors whose price is determined to be fair and reasonable. By skipping the tradeoff between technical and price, there is no need to evaluate the price proposals of the other offerors. This best-value technique allows technical capability to be prioritized over price. Subsequent competitive task orders will ensure proposed pricing is more accurately aligned to the proposed work.

- On-the-spot consensus: The evaluation team reads the proposal (or attends the oral presentation) together and then, as a group, evaluates the proposal and immediately documents the evaluation decision in real time before starting the evaluation of the next proposal. This results in a dramatically shortened time to award.

- Select best-suited, then negotiate: Once the government has completed its entire evaluation in accordance with the process established in the solicitation and has conducted its tradeoff analysis, the Government selects the apparently successful offeror/quoter to negotiate any remaining terms (technical and price) and finalize an award. Ideal for task/delivery orders under FAR subpart 8.4 and 16.505, but also for part 13 simplified acquisitions (incl. subpart 13.5 for commercial items). Not recommended for use under FAR part 15.

A FAR 2.0, same as the part 15 rewrite, will have unexpected negative consequences that permeate federal acquisitions going forward—too many variables are outside the FAR council’s control. By not specifying end-goals and how successful will be measured upfront, acquisition reform may not only fail, but also drag the system (further) down with it. As countless charlatans know, naming and blaming is easier than effecting positive change.

Comments ()